With the publication of my third Quaker Quicks book, Hearing the Light, I now have six published books and a few people have asked questions about what distinguishes them. It seems like a good time to share some observations about all my published books so far – especially who might want to read each of them.

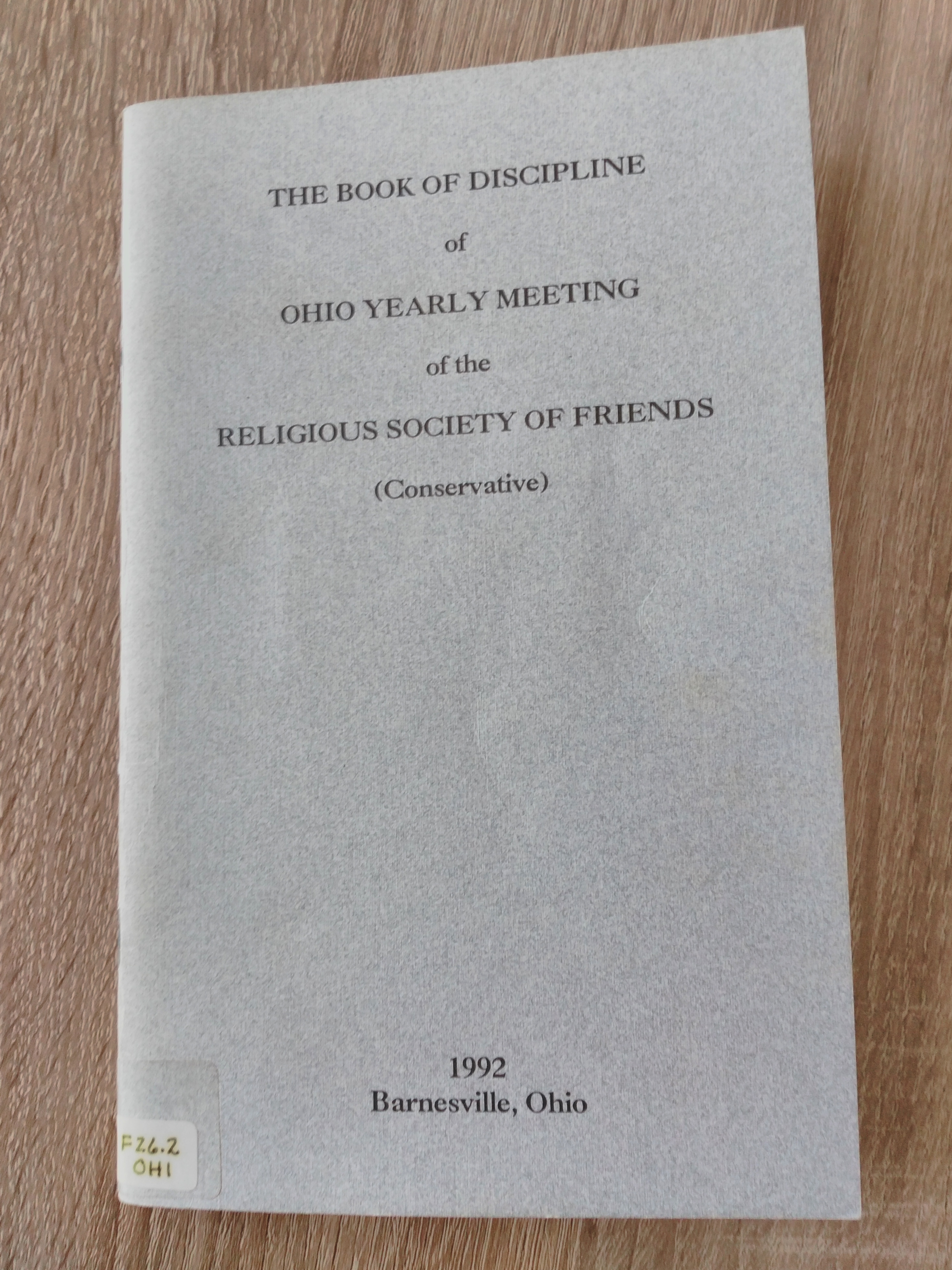

The two academic books, British Quakers and Religious Language and Theology from Listening, were both published by Brill. These are mainly for people who want all the references and the details. Practically, the price restricts readership to those with deep pockets and those with access to university libraries. The first one was based on the Quaker part of my PhD thesis and looks at how British Quakers use the list format as an inclusive way of naming God. The second one details my research on the core of liberal Quaker theology, based on a wide range of books of discipline and an analysis of some key popular and academic publications.

My first novel, Between Boat and Shore, was published by Manifold. It’s a lesbian love story set in Neolithic Orkney. Unfortunately, Manifold have now closed and the ebook is now unavailable, but you can still buy paperbacks from a few places, including the Quaker Centre bookshop and direct from me.

And that brings me to my Quaker Quicks books.

The first one, Telling the Truth about God, is about how British Quakers speak about the divine, some of the challenges involved, and how we use lists and other inclusive structures to both name and contain the diversity of theological views in the community. It’s based on my PhD research and my experience running workshops on the topic. It has two introductions, one for Quakers and one for everyone else, and might be of interest to anyone who has struggled with discussing the ineffable. For Christmas or other present-giving occasions, buy it for: Quakers who have questions about words, non-Quakers who have questions about Quaker nontheism, people who sit in worship services wondering what we could say instead of ‘Lord and Father’, anyone who reads ahead on the carol sheet and changes the words.

The second one, Quakers Do What! Why?, tries to give short and accessible answers to a wide range of commonly asked questions about liberal Quakers. It’s based on a lifetime’s experience of being asked questions about Quakers, from the ordinary to the strange, and trying to answer them quickly and clearly. It’s aimed at people who don’t yet know much about Quakers but want to know more, but it might also be useful for people who know some things already. If you’ve found this blog post by searching the internet for ‘Quakers’, and haven’t yet read much else, you could start with this book. If you’re thinking of buying for someone else, this book might be good for: that friend who doesn’t come to Quaker meeting but always asks questions about it, someone who’s come to meeting a few times and looks puzzled during the notices, people who seem like they would get ‘Quaker’ if they took an internet quiz about what religion to be.

The third and most recent one, Hearing the Light, is an attempt to describe the core of liberal Quaker theology. It argues that liberal Quakers do have a theology – one which is embodied in our practice of unprogrammed worship – and that enough of it is shared that it can be said to have a core. (Spoiler: the core is the process of watching for the Spirit moving.) It talks about how Quakers make decisions and why. It talks about how we know things, how we record and share what we know (especially through books of discipline/faith and practice), and how readers can experiment for themselves with Quaker ways of doing things. The main audience for this book is Quakers who want to explore our tradition further, but it will also be of interest to people who ask questions about why Quakers feel they can trust what they discern in meeting for worship for business. You might want to buy this book if: you have questions about the Quaker tradition and how worship and decision-making relate, you want to explore our worship process further, or you want to know more about liberal Quakers beyond your Yearly Meeting. It might make a good gift for someone getting further into the Quaker way, or someone with questions about Quaker discernment.

Of course, you can recommend all of them to your library! All three Quaker Quicks books would probably be a good fit for a local meeting library, and many other libraries will consider buying them if you ask. Similarly, asking for them at your local bookshop helps to raise the profile of the whole series and supports your local bookshop, so that’s good all round. You can also find them all on the usual online bookshops, including Amazon and Hive.

If you have other questions about these books or any of my other writing projects, please drop a comment below or come over to my Goodreads profile where you can ask questions for everyone to see.